Play, an Essential Superpower

April 10, 2020

When the Rain Stops…Redressing a “colour-blind” society in the midst of a cultural moment

June 2, 2020

We all have our unique lens by which we view and understand the world. And even if you are skeptical that our lenses are all that unique I think we can agree that our lenses are shaped in large part by our genetics, our upbringing, our cultural heritage, and particularly by the personal life choices we make. The ancient Greek philosopher Socrates is believed to have made the statement: “The Unexamined Life is Not Worth Living.” This is a powerful statement well worth unpacking for any of us not familiar with it.

If you are not new to this website and are familiar with my previous other posts it’s probably not a shock to you that the primary way that I examine and process the world around me is through my visual art practice. What may not be so obvious is the role words and language plays in shaping not only my own, but all of our perception of reality. In a very real sense what we say to ourselves, our inner mono-log, determines our perception of reality.

In a Ted X talk author, Charles Faulkner, poured table salt from one container into two separate clear glass jars, with the only difference being one jar was labeled salt and the other jar was labeled cyanide. Though it was clear to the viewers that both jars contained the same white crystal substance, salt poured out from the same source into equivalent containers; the mere act of labeling one jar cyanide was enough to create a different perception of reality in the viewers’ mind, triggering in many of the onlookers a visceral display of cognitive dissonance leading to a re-evaluation of their underlying beliefs and potentially a change in their behaviour. Something very powerful was happening on a subconscious level in the minds of the viewers.

Conceptual art, starting with the act of French artist Marcel Duchamp submitting a commercially manufactured urinal, that he titled Fountain, as a work of art in 1917 is art in which the artist’s concerns are first and foremost about the idea(or concept) rather than the finished object. Art by this measure is anything an artist calls art. Which is an idea, like our first illustration, that exposes how reality can be shaped by language and the imagination.

By his gesture, Duchamp was attempting to shift the balance of power as he saw it from the commercial art markets and the art institutions into the hands of the artists themselves by positioning the artists’ imagination as the only measure of value that counted.

Duchamp’s Fountain, submitted and signed under the pseudonym “R Mutt” was at the time rejected by the institutions and a majority of his peers as not being art, the designation it would still hold today were it not for the gradual and now full acceptance of the idea that anything an artist call’s art is art. This is a nod to the primacy of the imagination that even Albert Einstein echoes in his famous saying “Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited to all we now know and understand, while imagination embraces the entire world, and all there ever will be to know and understand.”

Fountain, of which we have several signed replicas commissioned by the artist several decades after the fact(the initial piece being lost to history, most likely disposed of by the artist himself) is arguably the most significant work of modern art today, and Duchamp’s ideas around art is the dominant perspective among contemporary artists today. The art markets and the art institutions, however, still yield at least as much power and enjoy even more authority than ever before in attributing value and significance to objects and ideas.

As far as I can tell, the art establishment has inevitably co-opted Duchamp’s initial anti-market and anti-institutional stance for their purposes. In the case of the market the motive being profit, and in the case of the institution the motive being influence and control of the narrative.

So what does all this have to do with my art practice, and more importantly why should we care?

Some of us might remember the scene in the Spike Lee movie Malcolm X when the American Muslim minister and human rights activist is guided in the early days of his conversion to examine the word black and the word white in the English dictionary, and is brought to the realization that the definition of these words are not neutral, as might be assumed but are constructed to reflect and reinforce the existing racialized social-political power structures of the time. Far less of us will be familiar with the similar observation made by Martin Luther King Jr and articulated pointedly in the following MLK quote:

“Somebody told a lie one day. They couched it in language. They made everything Black ugly and evil. Look in your dictionaries and see the synonyms of the word Black. It’s always something degrading and low and sinister. Look at the word White, it’s always something pure, high and clean. Well I want to get the language right tonight.

I want to get the language so right that everyone here will cry out: ‘Yes, I’m Black, I’m proud of it. I’m Black and I’m beautiful!”

Consider for a second the implications of the above observation in context with our earlier examples of the power of words to shape our perception. I described earlier how the mere act of labeling a known bottle of salt with the word cyanide challenged peoples’ perception of reality, triggering some people to subconsciously transfer the attributes of the false cyanide label to the actual content of the bottle of salt. Also both the artist Duchamp and the physicist Einstein made a case for the supremacy of the imagination to shape reality. And in the above description, I relayed how over half a century ago MLK demonstrated that the dictionary definition of the word black and the dictionary definition of the word white have been used within our society in a harmful manner to systematically transfer negative attributes to an entire segment of society, Black people, and transfer positive attributes to a different segment of society, White people.

This is a pretty important if not remarkable observation as it means that textbook definitions do reflect if not shape societal perception. And, if we are to address North America’s social divide, in particular as it pertains to race and ethnicity, our efforts would be largely inadequate if it didn’t address the effect of official language and words to shape, even subliminally, our perception of ourselves and others. This is a radical proposition that paints an even more challenging MLK than the accepted mainstream portrait.

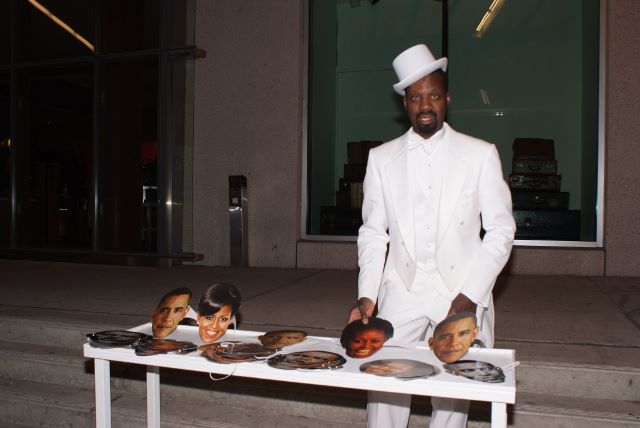

Selling Obama masks, depicted above, is a documentation of a performance piece, in which I am selling face masks of the President and the First lady of the United States of America, Barack and Michelle Obama, to a random crowd on various street corners days before the 2010 US midterm election.

The election of the first African American president of the United States was to a large extent the culmination of the Civil Rights movement and MLK’s “I have a dream” speech. Selling masks of the likeness of a Black president and a Black first lady was a time-specific conceptual interactive performance. The near-unanimous and enthusiastic reception of the masks by a largely White audience was an optimistic snapshot in time of the broader culture’s desire to embrace a different perception of Blackness, rejecting the implicit negative transfer of attributes embedded in language articulated in authoritative text like the dictionary, and circumventing the historical Western fear of Black gatherings, Black crowds, and Black neighbourhoods.

After all, dawning the mask metaphorically made us all one people. And for an instance that one Black people that we had all metaphorically become in dawning the Obama mask was the embodiment of the most powerful man and the most powerful woman on the planet.

Given our racialized history, this is a case of cognitive dissonance on a mass scale in a positive direction.