Conceptual Art and the Effect of Words to Shape Imagination and Our Perception

April 24, 2020

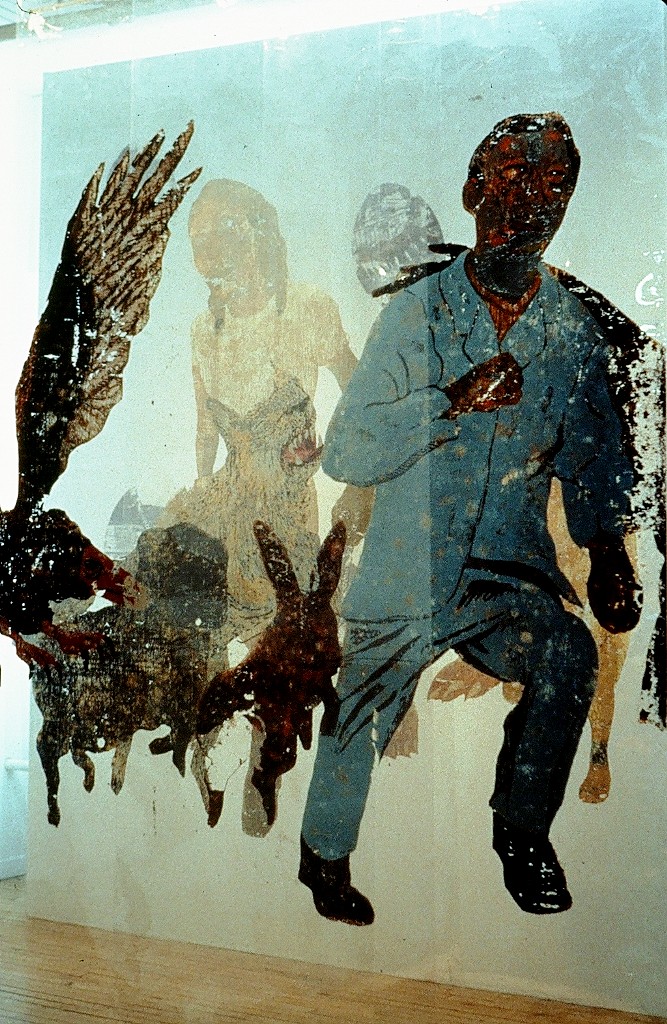

Shooting Gallery/Our National Pastime

June 24, 2020

As many of us remain at home quarantining ourselves to flatten the curve, a pattern is emerging from the barrage of daily news-feeds. You’ve probably seen the headlines: COVID19 disproportionately impacts Black and Brown people. A recent online Toronto Star article reads “African Americans account for 70% of the 86 recorded deaths” in Chicago “but made up 29% of the city’s population. Louisiana saw the same 70% of deaths among African-Americans who constituted just 32% of the population.”1

It’s tempting to see these racialized disparities as an American or even UK phenomenon, both countries with longer histories collect data that can disaggregate by race within health care, Canada’s health care system doesn’t. A common Canadian sentiment can be heard in a senior health official’s comment relayed on CBC radio’s The Current, and on U of T’s news website – “Canada is a colour-blind society and [we] shouldn’t expect that race-based data is necessary.”2 I beg to differ.

Digging into the weeds reveals unpleasant histories about our institutions and our cultural context as Canadians that dispels this popular narrative. (See links in footnotes 3, and 4 below)

In April 2019, Queen’s University issued a formal apology admitting that it had an official school policy within their medical department restricting Black students from enrolling in med school in order for the university to position higher within the American Medical Association(AMA), the organization that ranks medical schools in North America and better positions them for funding by institutions such as the Carnegie Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation. Other Canadian Universities- McGill, Dalhousie, and UofT had similar policies.3,4

What was striking about Queen’s was not only their late acknowledgment of the policy but that the ban which was enforced until 1965 was only rescinded in 2018.3,4 Let that sink in for a second…

It’s a comfortable thing for us here in Canada to point to racialized disparities in the US: health-care, wealth gaps, bad policing, and mass incarcerations without examining our own historical and cultural context. In my art practice, I tackle the uncomfortable by reflecting on our legacy of colonization and its effects on African-Canadian culture in the global economy. Through my art, I address the underpinnings of our often messy, and complex social interactions with disarming visual constructs, using creative methods oftentimes predicated on play, and interactivity.

Why is this important – well if we desire a society that treats all of its citizenry with dignity and one that affords everyone a level playing field so that all can compete equitably then we have to demand more from our institutions and of ourselves than the current status quo. This is my way of doing just that. Through my art practice, and blogging, I endeavor to shed light on pertinent but not widely disseminated histories that may help us better navigate the present.

In a month book-ended by video footages of the senseless murdering of two unarmed Black men – Ahmaud Arbery was intentionally gunned down in Georgia, by a former police officer and his son whose unsubstantiated citizen’s arrest.claim would have gone unchecked by law-enforcement had the recording of the encounter not been leaked several weeks later. Likewise, George Floyd was handcuffed then casually suffocated to death as his arresting officer kneeled on his neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds in Minneapolis, Minnesota, while faced down on the ground pleading for his life. This incident would have also gone unchecked had it not been for the footage.

How do these overt abuses of policing(Canada has its cases too) relate to official institutional barriers stifling Black student enrollment in Canadian med schools? They are symptoms of underlying systemic biases that persist only because we Canadians, like our neighbours to the south, may have not seen, may have ignored, or may have dismissed outright the “footages” in the past. This last month we were confronted with not one but two such footages that have stirred many of us. However, all the outpouring of emotions, all the coverage, and the rallying will be for naught if we do not address along with the overt racialized police brutality the more covert indicators of systemic biases and unconscious biases.

What do I mean? Of the 259 U of T medical school graduates, graduating this year only one, Chika Oriuwa the class valedictorian, is Black.5 As sad as the implications of racialized educational and law enforcement disparities maybe they are far from shocking to us who live it. The lack of Black academic and professional representation in Canadian society is of no surprise to any African Canadian that has gone through the Canadian public school system.

In contrast, my 3 years of living in Los Angeles(by no means a bastion of racial impartiality – read Rodney King beating) in which I pursued a masters degree at UCLA allowed me to come into contact with more Black people in academic and professional roles of authority(doctors, industry directors, professors) than in 18 years of going through the public education system followed by 7 years in the workforce in Canada’s most diverse city. The relative population of Black people in both cities are comparable: 8.7% in Los Angeles in 2010 compared to 8.9% in Toronto in 2016.

To be fair U of T like Queens does seem to be trending in the right direction in large part due to the work of the Black Student Application Program (BSAP). U of T’s medical schools graduating class of 2022 and 2023 have 14-15 Black candidates, respectively,5 and a historic number – 24 – of incoming Black medical students.6

We’ll never know the countless others, would-be doctors, engineers, architects, professors, etc of African ancestry that have fallen through institutional filters not designed for people that look like Oriuwa or myself.

Choosing to believe that such racialized disparities are just natural occurrences is simply choosing to not look at the “footage,” nor is it asking our institutions and ourselves the uncomfortable questions that will redress Canada’s history of racialized biases.

When the Rain Stops, pictured above, is a print media art installation that presents societal ills, often systematically visited on Black bodies, as vignettes falling like rain droplets or tears on an unlikely and diverse set of characters. The artwork suggests, like the proverbial saying – This too shall pass – a time when the present rain or tears will give way to joy.

- https://www.thestar.com/opinion/2020/04/08/unlike-canadians-americans-at-least-know-how-black-people-are-faring-with-covid-19-very-badly.html

- https://www.utoronto.ca/news/covid-19-discriminates-against-black-lives-surveillance-policing-and-lack-data-u-t-experts

- https://www.universityaffairs.ca/features/feature-article/when-black-medical-students-werent-welcome-at-queens/

- https://healthsci.queensu.ca/blog/1918-ban-black-medical-students-addressing-our-past-discrimination-promote-diversity-future?fbclid=IwAR3oTIHWl-izQl2b3GbQAESiUk0GAK-VkscQ73y1SCIosRoGtYcoX2lgUe4

- https://www.thestar.com/opinion/contributors/2020/05/28/the-only-black-medical-student-in-a-u-of-t-class-of-259-chika-oriuwa-graduates-as-valedictorian.html

- https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=263672978386484

2 Comments

Stephen as always a true artist at heart with strong convictions on justice and equality for all people regardless of race, color or social background. Thank you for this very insightful article and educating us on this pressing matter.

Good to hear from you Jane…we need to tell more of the Canadian perspective